Introduction

The LDH test (Lactate Dehydrogenase test) is a commonly used laboratory investigation that helps clinicians assess cell damage and tissue injury anywhere in the body. LDH is an enzyme present inside almost all cells, where it plays a role in energy production. Under normal conditions, only small amounts circulate in the blood.

When cells are injured or destroyed, LDH leaks into the bloodstream. Because LDH is found in many organs—including the heart, liver, lungs, kidneys, muscles, and blood cells—the test is non-specific, but it still provides valuable clinical insight when interpreted alongside symptoms, imaging, and other laboratory findings.

What is LDH (Lactate Dehydrogenase)?

LDH is an enzyme involved in cellular energy metabolism. It helps convert lactate to pyruvate and back again, a process that becomes especially important when tissues are under low-oxygen conditions.

From a laboratory perspective, LDH is important not because of what it does inside the cell, but because of what its presence in blood indicates. When cell membranes are disrupted—due to injury, inflammation, reduced oxygen supply, or disease—LDH escapes into circulation. Elevated blood levels therefore act as a general signal of tissue damage, rather than pointing to one specific disease.

Where is LDH Produced in the Body?

LDH is not produced by a single organ. Instead, it exists naturally inside cells throughout the body. Higher concentrations are found in:

- Heart

- Liver

- Kidneys

- Lungs

- Skeletal muscles

- Red blood cells

Different tissues contain different LDH isoenzymes. In certain clinical situations, measuring these isoenzymes can help suggest which organ system is involved, although total LDH is more commonly used in routine practice.

Main Functions and Importance of LDH

1. Energy Production

LDH supports cellular energy generation by helping cells adapt when oxygen availability is reduced. This function is essential in metabolically active tissues and during periods of physiological stress.

2. Marker of Tissue Damage

LDH enters the bloodstream when cells are damaged or destroyed. For clinicians, an elevated LDH level signals that cell injury is occurring somewhere in the body, prompting further evaluation.

3. Cancer Marker

LDH is frequently used as a prognostic and monitoring marker in several cancers, including lymphomas, leukemias, germ cell tumors, and advanced metastatic disease. Rising levels often reflect increased cell turnover or tumor burden rather than serving as a diagnostic marker on their own.

4. Diagnostic and Monitoring Tool

LDH supports clinical decision-making in a wide range of conditions, such as liver disorders, lung diseases, blood cell destruction, inflammatory states, and cancer follow-up. Its greatest value lies in trend monitoring rather than isolated measurements.

Causes of Low LDH Levels

Low LDH levels are uncommon and usually not clinically significant. In most individuals, they do not indicate disease.

Occasionally, laboratory interference—such as high Vitamin C intake—or rare inherited enzyme deficiencies may result in lower values, but these situations are infrequent in routine clinical practice.

Symptoms of Low LDH

Low LDH levels typically cause no symptoms. When rare enzyme deficiencies are present, individuals may notice exercise-related fatigue or muscle discomfort, but such cases are uncommon.

Causes of High LDH Levels

Elevated LDH reflects cell injury or increased cell turnover. Because LDH is widely distributed, many conditions can raise its level.

Cardiac injury, liver disease, blood cell breakdown, muscle damage, lung disorders, kidney injury, severe infections, and many cancers can all lead to increased LDH. In oncology, higher LDH levels often correlate with disease activity rather than pointing to a specific tumor type.

Transient elevations may also occur after intense physical exertion or acute illness.

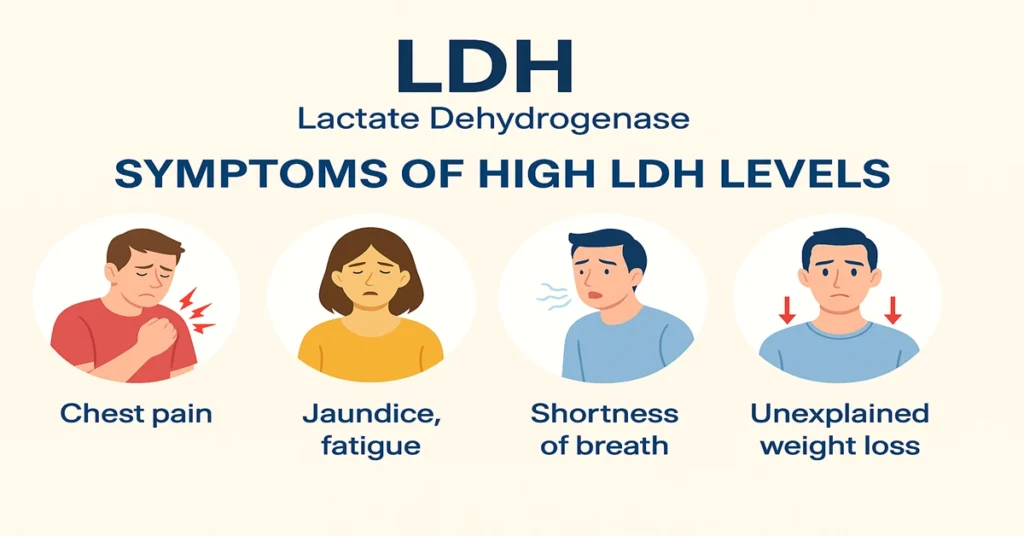

Symptoms of High LDH

LDH itself does not cause symptoms. Any symptoms present arise from the underlying condition responsible for cell damage. These may include chest discomfort, fatigue, breathlessness, jaundice, weakness, or unexplained weight loss, depending on the organ system involved.

Reference Ranges of LDH (Lactate Dehydrogenase)

Normal LDH ranges vary slightly between laboratories, but typical values are:

- Adults: approximately 140–280 U/L

- Newborns: higher levels are normal in early life

LDH isoenzyme patterns may sometimes help localize tissue involvement, but total LDH trends are more commonly used in routine monitoring.

Sample Type

- Sample type: Serum (blood)

- Tube used: Red-top (plain) tube

- Test type: Enzyme activity measurement

- Fasting: Not required

Test Preparation

No special preparation is usually required. Because LDH can rise temporarily after strenuous physical activity or during acute illness, clinicians may consider recent events when interpreting results. Any supplements or ongoing medical conditions should be disclosed at the time of testing.

When to Consult a Doctor

Medical consultation is appropriate if LDH levels are persistently elevated without an obvious explanation, or when LDH is being used to monitor a known condition such as anemia, liver disease, lung disease, or cancer. Symptoms such as unexplained fatigue, chest discomfort, jaundice, or weight loss should always prompt further evaluation.

Important Word Explanations

- LDH (Lactate Dehydrogenase): Enzyme released into blood when cells are damaged

- Isoenzymes: Different forms of the same enzyme found in specific tissues

- Hemolysis: Breakdown of red blood cells

- Cirrhosis: Long-term scarring of the liver

- Lymphoma: Cancer of the lymphatic system

- Myocardial Infarction: Medical term for heart attack

~END~

Related Posts

None found