Lactate Serum Test: High–Low Levels, Causes, Symptoms & Clinical Importance

Overview

Oxygen plays a central role in how the body produces energy. Under normal conditions, glucose is broken down using oxygen to meet the energy needs of cells, muscles, and vital organs. When oxygen supply is reduced, or when energy demand suddenly increases beyond what oxygen delivery can support—such as during severe infection, shock, or intense physical stress—the body shifts to an alternative pathway. This process results in the production of lactate.

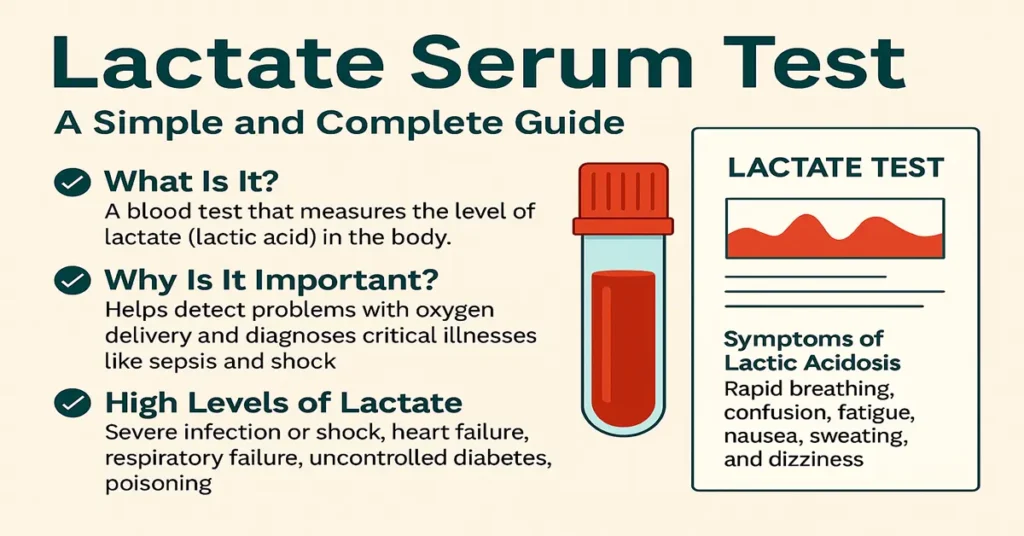

The Lactate Serum Test measures the amount of lactate circulating in the blood at a given time. From a clinical point of view, rising lactate levels often act as an early signal that tissues may not be receiving adequate oxygen or are under significant metabolic stress. Because of this, the test is widely used in emergency and critical care settings, particularly in conditions like sepsis, shock, heart failure, respiratory compromise, severe dehydration, and certain metabolic disorders.

Interpreting lactate values helps clinicians judge the severity of illness, recognize potentially life-threatening situations early, and monitor how the body is responding over time.

What Is the Lactate Serum Test?

The Lactate Serum Test is a blood test that determines the concentration of lactic acid in the bloodstream. Lactate is produced when cells generate energy through anaerobic metabolism, meaning energy production without sufficient oxygen.

In practical terms, when oxygen delivery is adequate, lactate production remains low. When oxygen delivery is impaired or energy demand is excessive, lactate production increases. Clinicians use this test to identify early tissue hypoxia, assess critical illness, support the diagnosis of lactic acidosis, and monitor trends during acute care.

Persistently high lactate levels suggest that the body is struggling to meet its metabolic demands and warrant careful clinical attention.

Where Is Lactate Produced in the Body?

Lactate is formed inside cells during glycolysis, the process by which glucose is broken down for energy. This mainly occurs in the cytoplasm when oxygen availability is limited.

Several tissues contribute to lactate production. Muscles generate lactate during intense activity or reduced oxygen supply. Red blood cells continuously produce lactate because they lack mitochondria and rely entirely on anaerobic metabolism. Brain tissue may also contribute during periods of seizures or significant metabolic stress.

Once produced, lactate is cleared primarily by the liver, where it is converted back into glucose through the Cori cycle. The kidneys also play a role in lactate handling and acid–base balance. Therefore, elevated lactate levels may reflect increased production, reduced clearance, or a combination of both.

Why Is This Test Important?

In clinical practice, the Lactate Serum Test is a key indicator of physiological stress. One of its most important uses is the early detection of impaired oxygen delivery to tissues. Lactate often rises before other signs become obvious, making it a valuable early warning marker.

The test supports the diagnosis of serious conditions such as sepsis, different forms of shock, cardiac or respiratory failure, and major blood loss. Serial lactate measurements are also used to monitor response during treatment, as falling levels often suggest improving tissue perfusion. Higher lactate concentrations are generally associated with greater illness severity, particularly in critically ill patients.

Beyond emergencies, lactate can also reflect metabolic strain related to exercise, illness, or toxin exposure, helping clinicians interpret the broader clinical picture.

Causes of Low Lactate Levels

Low or normal lactate values are common and usually reflect healthy metabolism. They are typically seen when oxygen delivery is adequate, lactate clearance by the liver and kidneys is effective, and overall metabolic balance is maintained.

From a laboratory perspective, low lactate levels are considered normal findings and do not indicate disease.

Symptoms of Low Lactate

Low lactate levels do not cause symptoms and are not clinically significant. Most individuals with normal lactate values feel entirely well, and no specific health effects are associated with low readings.

Causes of High Lactate Levels

Elevated lactate levels, also known as hyperlactatemia, occur when lactate production exceeds clearance. This can happen in a range of situations, from temporary physiological stress to serious medical emergencies.

In acute care, high lactate is commonly associated with severe infections, various forms of shock, respiratory failure, heart failure, major blood loss, severe anemia, and organ dysfunction—particularly involving the liver or kidneys. Metabolic disturbances such as uncontrolled diabetes or diabetic ketoacidosis may also contribute.

Lactate can rise in non-emergency situations as well, including intense physical exercise, prolonged seizures, severe dehydration, or exposure to certain toxins or medications. In each case, the laboratory value reflects underlying metabolic strain rather than an isolated abnormality.

Symptoms of High Lactate Levels

Symptoms associated with elevated lactate depend on the underlying condition. Patients may present with rapid or deep breathing, confusion, fatigue, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, or pale and clammy skin.

At higher levels, signs of more severe illness may appear, such as low blood pressure, reduced organ function, or altered consciousness. Clinicians view significantly elevated lactate as a marker that requires prompt evaluation, as it can progress quickly if the underlying problem is not addressed.

Reference Ranges

Serum lactate values are generally interpreted as follows:

- Normal: 0.5 – 2.2 mmol/L

- Elevated: Above 2.2 mmol/L

- Critical: Above 4.0 mmol/L

Levels exceeding 4 mmol/L are strongly associated with serious conditions such as severe sepsis, shock, or organ failure. Interpretation always takes the patient’s clinical condition into account.

Sample Type

The test is performed on a blood sample, using either serum or plasma. Venous blood is commonly used, while arterial samples may be taken in certain situations for more detailed assessment of oxygenation.

Proper collection technique is important, as prolonged tourniquet use or excessive fist clenching can falsely raise lactate levels.

Test Preparation

In most situations, no special preparation is required. Patients may be asked about recent intense exercise, alcohol intake, existing conditions such as diabetes or liver disease, and medications that could influence lactate levels. In emergency settings, the test is performed immediately without preparation.

When to Consult a Doctor

Medical evaluation is advised if symptoms such as persistent fever with confusion, rapid breathing, chest discomfort, severe dehydration, or unexplained weakness occur. Emergency care is essential if there is loss of consciousness, seizures, very low blood pressure, or signs of shock. Rising or persistently high lactate levels are treated as clinically significant findings that require urgent attention.

Important Word Explanations

- Lactate: A substance produced when energy is generated without enough oxygen

- Anaerobic Metabolism: Energy production in the absence of adequate oxygen

- Sepsis: A severe, body-wide response to infection

- Shock: A state of dangerously reduced blood flow to tissues

- Hypoxia: Reduced oxygen supply to tissues

- Lactic Acidosis: Harmful accumulation of lactate causing acid–base imbalance

~END~

Related Posts

None found