Iron (Serum Iron) Test: Meaning, Functions, Low & High Levels, Normal Range, Symptoms & Complete Guide

Overview

The Iron Test, commonly referred to as the Serum Iron Test, measures the amount of iron circulating in the bloodstream at the time of testing. Iron is a critical mineral for normal blood formation, particularly for the production of hemoglobin, the oxygen-carrying protein inside red blood cells.

From a clinical perspective, serum iron helps doctors understand whether the body has enough circulating iron available for red blood cell production or whether iron is accumulating beyond normal limits. The test is most often interpreted as part of a broader iron study panel, alongside ferritin, transferrin, and total iron-binding capacity (TIBC), rather than in isolation.

What Is Iron and Why Is It Important?

Iron is an essential element involved in oxygen transport, cellular energy production, and several enzyme-driven processes. Most of the body’s iron is locked inside hemoglobin within red blood cells, while smaller amounts are present in muscles and stored in organs such as the liver, spleen, and bone marrow.

Clinically, iron balance is delicate. Too little iron limits hemoglobin production and reduces oxygen delivery to tissues. Too much iron, on the other hand, can accumulate in organs and gradually impair their function. This is why iron levels are closely regulated and carefully interpreted in medical practice.

Where Is Iron Processed or Regulated in the Body?

Iron is not produced by the body and must be obtained from dietary sources. After ingestion, iron is absorbed primarily in the upper small intestine. The amount absorbed depends on the body’s current iron requirement rather than simple intake alone.

Once absorbed, iron binds to transferrin in the blood and is delivered to tissues that need it, particularly the bone marrow for red blood cell production. Excess iron is stored safely in ferritin form within the liver and other tissues. This tight regulation helps prevent both deficiency and overload, making disturbances in iron levels clinically meaningful.

Iron Absorption and Transport

Iron handling in the body follows a controlled pathway. Absorption in the intestine adjusts according to demand, storage organs act as reserves during periods of low intake, and transferrin ensures iron reaches the right tissues at the right time.

From a laboratory standpoint, serum iron reflects the circulating portion of this system, not total body iron. This is why doctors rarely rely on serum iron alone when assessing iron status.

Main Functions and Importance of Iron

Iron’s primary role is supporting hemoglobin formation, allowing red blood cells to transport oxygen efficiently. It also contributes to muscle oxygen storage through myoglobin, supports energy generation within cells, and plays a role in immune defense and neurological function.

Because iron participates in so many core processes, disturbances often present as general symptoms such as fatigue or reduced exercise tolerance rather than organ-specific complaints in early stages.

Causes of Low Iron Levels (Iron Deficiency)

Low iron levels usually reflect a mismatch between iron intake, absorption, and loss. In clinical practice, iron deficiency is most often linked to chronic blood loss, increased physiological demand, or impaired absorption rather than sudden dietary changes.

Doctors consider factors such as menstrual blood loss, gastrointestinal bleeding, pregnancy, chronic inflammation, and digestive disorders when interpreting low serum iron results.

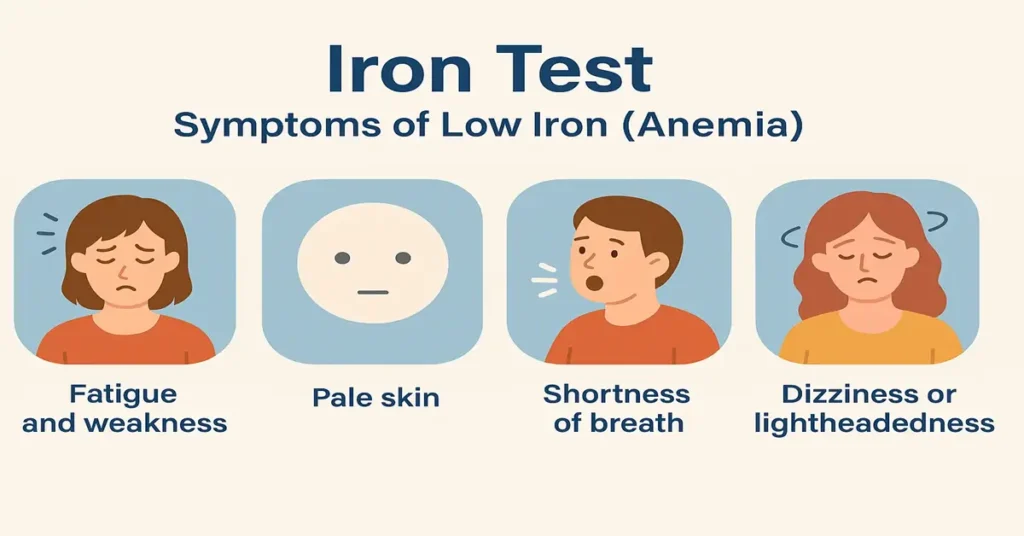

Symptoms of Low Iron Levels

When circulating iron is insufficient, the bone marrow cannot produce optimally functioning red blood cells. This results in reduced oxygen delivery, which commonly presents as tiredness, weakness, or shortness of breath.

Symptoms usually develop gradually. Many patients remain asymptomatic until iron deficiency becomes more advanced, which is why laboratory testing plays a central role in detection.

Causes of High Iron Levels (Iron Overload)

Elevated serum iron suggests increased absorption, excessive iron release from red blood cells, or impaired storage regulation. One important cause is hereditary hemochromatosis, where the body absorbs more iron than it needs over time.

Other clinical scenarios include repeated blood transfusions, liver disease, or inappropriate iron supplementation. Persistently high iron levels raise concern because excess iron can deposit in organs and disrupt normal cellular function.

Symptoms of High Iron Levels

Iron overload often develops silently. Early symptoms, when present, tend to be non-specific, such as fatigue or joint discomfort. As iron accumulates over time, organ-related manifestations involving the liver, heart, or endocrine glands may appear.

Because symptoms are often subtle initially, laboratory findings are crucial for early recognition.

Reference Ranges for Iron Levels

Serum iron reference ranges vary slightly between laboratories and are influenced by age and sex:

- Men: 65 – 175 µg/dL

- Women: 50 – 170 µg/dL

- Children: 50 – 120 µg/dL

Clinicians interpret these values alongside ferritin and transferrin studies to avoid misclassification based on temporary fluctuations.

Sample Type and Test Information

- Sample Type: Serum

- Tube Used: Red Top (Plain Tube)

- Fasting: Typically recommended

- Timing: Morning samples are preferred due to natural daily variation

Serum iron levels can change throughout the day, which is why consistency in sample timing improves accuracy.

Test Preparation

Fasting before testing helps minimize short-term dietary effects on serum iron. Patients are usually advised to temporarily withhold iron supplements and inform the laboratory or physician about ongoing medications, as several drugs can influence iron measurements.

Normal hydration should be maintained, and the test is best performed under routine conditions rather than during acute illness unless clinically indicated.

When to Consult a Doctor

Medical review is advised when iron levels are persistently abnormal or when symptoms such as fatigue, breathlessness, or unexplained weakness are present. A family history of iron disorders, unexplained liver abnormalities, or anemia also warrants evaluation.

Doctors typically correlate iron results with clinical findings and may request additional tests rather than acting on serum iron alone.

Important Word Explanations

Hemoglobin

The oxygen-carrying protein within red blood cells.

Ferritin

A storage protein that reflects the body’s iron reserves.

Transferrin

A blood protein that transports iron to tissues.

Anemia

A condition marked by reduced oxygen-carrying capacity of blood.

Hemochromatosis

A genetic disorder causing excessive iron absorption.

Myoglobin

A muscle protein that stores oxygen for muscle activity.

~END~

Related Posts

None found

Pingback: MCHC Test – Normal Range, Low & High Levels, Causes and Symptoms